If you are a small business owner or an individual who works or even claimed a deduction for a child on your tax return, the IRS may go to great lengths to scrutinize your tax filings. This is particularly true if you are successful and earn any income. The more successful you are, the more scrutiny you are likely to get.

While the IRS focuses on small business owners and working individuals, there are those who simply file fraudulent tax returns and the IRS issues them large checks without any verification whatsoever. Tax revenues just fly out the back door. And we are not talking about small sums. The sums are often sizable. And this has been going on for many decades. Most cases only come to light if the IRS happens to catch wind of the issue, which is not all that often, and if the IRS actually pursues criminal charges, which it doesn’t do that often.

The reported cases consist primarily of those who are in prison and file refund claims. They have nothing to lose by having new criminal charges so criminal tax laws may not be a deterrent. The IRS has paid out thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of false refund claims to prisoners. But this type of fraud isn’t limited to prisoners. The IRS also pays out millions of dollars, if not hundreds of millions, to others–all with no verification whatsoever. The recent United States v. Kock, Nos. 22-1368, 22-1576 (8th Cir. 2023) is an example, and it may leave you wondering why you are working so hard to earn a living when the IRS is simply giving away money to anyone who asks for it.

Contents

Facts & Procedural History

The defendant had ongoing troubles with the IRS for more than a decade. He stopped filing tax returns in 2009, despite receiving W-2 forms from his employers every year.

In 2019, Kock filed a fraudulent Form 1041 in the name of the Jeffrey Allan Kock Trust, claiming a refund of $20,671. The IRS issued a Treasury check in that amount, which Kock deposited into an account at Bankers Trust. In early 2020, Kock filed a second fraudulent Form 1041 in the name of the Trust, seeking an additional refund of $10,921,192. The IRS issued a check in that amount, which Kock also deposited into his Bankers Trust account.

In February 2020, Kock used some of the money to purchase two Mercedes Benz vehicles, a 2020 E63 sedan, and a 2017 G63 SUV. The following month, Kock unsuccessfully attempted to apply $75,000 from the Bankers Trust account to Iowa Realty to purchase a multi-million-dollar home.

Concerned by Kock’s unusual banking activity, Bankers Trust arranged a meeting with him. During the meeting, Kock acknowledged receiving the Treasury checks and described the tax system as “a game of monopoly.” Kock was so unconcerned about the IRS that he didn’t even bother trying to ferret his tax refund proceeds off to a foreign country or put it beyond the IRS’s reach. He left it sitting in his bank account.

Bank officials contacted the IRS and law enforcement about their conversations with Kock. The IRS determined that the refunds had been paid in error and asked Bankers Trust to return the funds. Bankers Trust froze Kock’s account and later returned to the IRS the amount in the account.

In April 2021, Kock was indicted on five counts of failure to file a tax return, two counts of making false claims against the United States, wire fraud, mail fraud, three counts of money laundering, and concealment of an asset. The IRS was able to recoup some of the proceeds that it gave away to Kock.

How the IRS Selects Returns for Audit

If you pay taxes and read the facts of the case above, you are probably upset. If you pay significant amounts of taxes each year and forego necessities or make sacrafices to do so, you are probably even more upset. Justifiably so.

To understand how and why such blatant and obvious refund fraud can even occur in the first place, we need to consider how the IRS selects returns for audit, as audits are how the IRS catches most tax fraud.

Since the U.S. tax system is built around the concept of voluntary tax return filing, the IRS typically reacts to returns submitted by taxpayers. Most tax problems are not discovered as they are not reported to the IRS. This is why the IRS encourages others to file information reporting forms to the IRS, such as employers issuing Forms W-2 or 1099, brokerage companies issuing Forms 1099, etc. These information reporting forms alert the IRS to potential tax due. Self-filed returns are then used to select those for audit and represent most, nearly all, of the tax returns that are examined. So the first bobble of the baton. It happens when the IRS doesn’t even see taxable transactions as no tax return is filed. The message is no-tax-return-filed-no-problem.

The second bobble of the baton happens for those returns that are filed. Most of these returns go through a “classification” process. This is the internal process by the IRS whereby tax returns are scored or identified for problems and audit potential. They are also selected through a matching process whereby returns are compared to information returns that were filed with the IRS by third parties. While the details and functions of some of these processes are closely guarded by the IRS, others are set out and described in the IRS policy manual and other guidance.

The IRS uses the phrase “large, unusual, and questionable” or LUQs to describe the issues it looks for. This policy results in returns with some issues being pulled for audit more than others. Tax losses are an example. The IRS frequently pulls tax losses for audit as they are often large and often unusual in that most taxpayers do not take tax losses every year.

For the cases that are actually worked by IRS auditors or that end up in appeals, those that result in significant refunds are referred to the Joint Committee on Taxation for review. There is no such review for refunds that are just issued without being examined by an IRS auditor. The audit rate and chances of being pulled for audit are low. Very low. This is the second bobble of the baton. The facts described above for the Kock case are an example of this type of bobble. The tax return that is filed is simply processed with no one looking at it, and the computer systems process it as a matter of course.

Getting an IRS Refund

This is the other frustrating aspect of the large refund checks that the IRS issues like this. There are taxpayers who are legitimately owed money and entitled to refunds and they cannot get the IRS to issue checks to them.

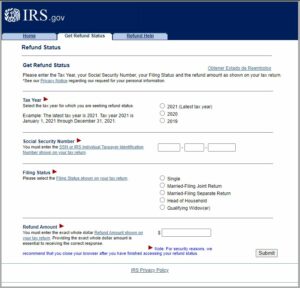

Assuming that the IRS actually owes you a refund and hasn’t paid it to you, the IRS has a “Where’s My Refund” page on its website. You can use this to see what the status of your refund is.

If this does not help, the next step is to get your IRS “account transcript” to see what the latest status is. You can get these by visiting the “Get an IRS Transcript” page on the IRS.gov website.

If that fails or doesn’t provide an adequate answer, your next step is to call the IRS’s 800 phone number. If that fails, your next step is to contact the IRS Taxpayer Advocate Service.

Refunds in Excess of Tax Payments

Tax refunds are typically limited to the amount of tax paid, so you might assume that the losses from fraudulent refunds are also limited to the amount of tax the taxpayer paid. However, as demonstrated in the Kock case, this is not always the case.

Kock’s trust likely did not pay $10 million in taxes, yet it received a refund of that amount, which came from other taxpayers’ contributions. Think about that. If you paid in taxes to the IRS in 2020, the IRS took your money and gifted it to Kock.

If you are unfamiliar with the IRS, this may seem confusing. How could the IRS issue a refund to someone in excess of the amount they paid to the IRS? You may view a taxpayer’s account with the IRS as a checking account that cannot go negative. That isn’t how it works. The IRS frequently pays out more to taxpayers than they pay in. This is very common.

Congress authorizes the IRS to pay out more to taxpayers than they paid in. This is usually through “refundable tax credits.” For example, the earned income tax credit is a refundable credit intended for low-income taxpayers. These earned income tax credits can (and often do) result in the taxpayer receiving a refund in excess of the taxpayer paid to the IRS for the year (that our tax system does not even require most Americans to actually pay in any income taxes each year is yet another issue that gets little attention). These tax credits, particularly those for lower-income workers, can add up to significant amounts overall, though on an individual basis, they are often just a few thousand dollars each year.

There are also larger refundable tax credits, such as the employee retention credit, which is a payroll tax credit (not an income tax credit) that was created to get money to employers to pay their workers during COVID-19. This credit was intended to result in large refunds being issued to keep businesses going during COVID-19 and was sprung on the IRS with little notice, making it more difficult for the IRS to set up processes to detect this type of payroll tax fraud.

However, the fraud in cases like Kock’s case likely did not involve a refundable credit. It was likely just a simple return that reported expenses in excess of income, resulting in a $10 million dollar refund. It may have even listed that the trust made $10 million of prepayments to the IRS even though they were never paid to the IRS.

You might think that hey, the IRS knows what a taxpayer paid to it. It can just match the payment to the tax return, right? That would stop refunds from being issued like this, right? Maybe. This just isn’t within the IRS’s capability.

The Takeaway

The Kock case highlights the fact that tax refunds are not always limited to the amount of tax paid, and fraudulent refunds can come at the expense of other taxpayers who actually pay taxes. While the IRS goes to great lengths to scrutinize small business owners and individuals who claim deductions and try to unwind legitimate tax planning, fraudulent refunds can slip through undetected, resulting in tax revenues being lost. This brazen and blatant fraud undermines the public trust in the IRS and the integrity of the system. It is unfair. Grossly unfair. While most taxpayers–the few who actually pay any taxes each year–are honest, they end up paying more than their fair share of taxes given that they have to fund the IRS’s inability to not issue fraudulent refunds.

In 40 minutes, we'll teach you how to survive an IRS audit.

We'll explain how the IRS conducts audits and how to manage and close the audit.