There are several issues that the IRS frequently challenges on audit. For individual taxpayers, this includes moving expenses.

Taxpayers are entitled to deduct moving expenses. Our tax laws impose several limitations on what expenses can be deducted and when.

The recent Doyle v. Commissioner, Docket No. 6532-20S (2021) case provides an opportunity to consider these rules. This is an area where advanced tax planning can help ensure that the tax deduction is allowable.

* Note: The moving expense deduction was eliminated for most taxpayers starting in 2018 as part of the tax reform laws. Congress made this change as part of the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (“TCJA”). For tax returns starting in 2018, this tax reform limits this deduction to members of the military. If you (or your spouse) are a member of the Armed Forces on active duty and, due to a military order, you move because of a permanent change of station the tax reform does not limit your moving expense deduction. You can still deduct moving expenses. But for most taxpayers, moving expenses are not deductible currently. It should be noted that moving expenses may still qualify as a business expense and be deductible under Section 162 for businesses and some business owners. There are special considerations for employees who receive reimbursements for moving expenses too. Reimbursements for moving expenses may or may not be taxable. If you own a business and pay moving expenses or receive reimbursements for moving expenses, you should talk to your tax attorney about this deduction.

Contents

Facts & Procedural History

The taxpayer’s husband accepted a job in Hawaii. He moved to Hawaii and was employed there for a few months.

The taxpayer’s wife and children stayed in California. Before they moved to Hawaii, the taxpayers decided Hawaii was too dangerous for their family.

The taxpayer’s husband moved back to California.

The IRS audited the taxpayer’s return. It disallowed the moving expense deduction for the move to Hawaii and back to California. We’ll come back to these facts in a minute.

Can You Deduct Moving Expenses?

We are often asked whether moving expenses can be deducted on tax returns. Our tax laws say that moving expenses are deductible for income tax purposes. This has not changed. Even the significant changes in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (“TCJA”) did not change this law.

You can claim moving expenses on the first page of your tax return. This moving expense deduction is an above-the-line deduction. This means that the taxpayer can take the standard deduction in addition to the moving expense deduction. It also means that taxpayers do not have to take itemized deductions to be able to claim the moving expense deduction.

The moving expense deduction is limited by the type of expense and the rules impose several tests that have to be met.

What Expenses Count as Moving Expenses?

There is no definitive list as to what counts as a moving expense. Section 217 says that moving expenses include costs to:

- Move household goods and personal effects from the former residence to the new residence and

- Travel (including lodging) from the former residence to the new place of residence.

This includes mileage for a vehicle. The mileage expense can be computed using the standard mileage rate for moving expenses or the actual costs incurred.

Section 217 also says costs for meals incurred while traveling do not count as moving expenses. Last, Section 217 says that the expense has to be reasonable.

The moving expense deduction generally has to be taken within one year from the date they started the new job.

The court has confirmed that this deduction is available even if the taxpayer moves to a foreign country and the income to be earned in the foreign country is not subject to U.S. income tax. See Hartung v. Comm’r , 55 T.C. 1 (U.S.T.C. 1970).

The Two Distance Tests

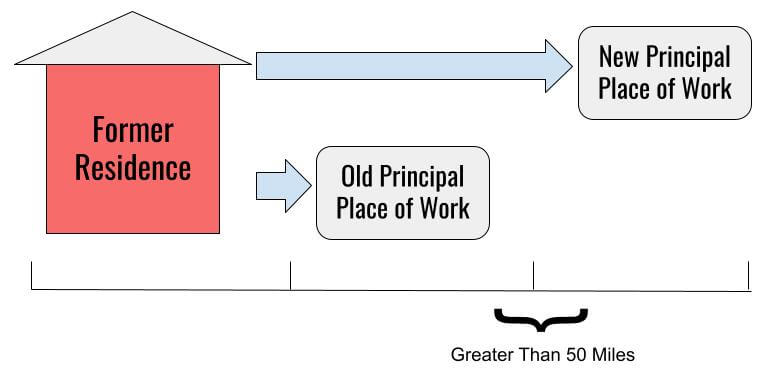

Section 217 limits the deduction for moves to start a new job or self-employed business. It also sets out two distance tests.

To be deductible for income tax purposes, the move has to satisfy one of the two distance tests:

- The taxpayers principal place of work has to be at least 50 miles father from his former residence than was his former principal place of work or

- The taxpayer had no principal place of work and his new principal place of work is at least 50 miles from his former residence.

These tests are usually easily met when there is a long-distance move. This case is an example. In the present case, the distance tests were met for the move to Hawaii as the taxpayer husband moved from California. Hawaii is more than 50 miles from California.

These distance tests can be more difficult to meet when a taxpayer changes jobs within the same metropolitan area. Take Houston metropolitan area, for example. Because traffic is so bad in Houston, it is common for Houstonians to move to be closer to their primary work location. One may live and work in Katy, Texas (East side of Houston) and take a job in Baytown, Texas (West side of Houston). These areas are right at 50 miles apart.

The Two Work Longevity Tests

In addition to the two distance tests, Section 217 sets out two work longevity tests. One of these tests has to be met for the moving expenses to be deductible:

- During the 12-month period immediately following his arrival in the general location of his new principal place of work, the taxpayer is a full-time employee, in such general location, during at least 39 weeks, or

- During the 24-month period immediately following his arrival in the general location of his new principal place of work, the taxpayer is a full-time employee or performs services as a self-employed individual on a full-time basis, in such general location, during at least 78 weeks, of which not less than 39 weeks are during the 12-month period referred to in # 1, above.

These longevity tests raise difficult questions as to what the “general location” is when the taxpayer only moves 50 miles. Take the prior example of a taxpayer who lives and works in Katy, Texas (East side of Houston) and takes a job in Baytown, Texas (West side of Houston). Is Katy and Bayton the same “general location?” They are both considered part of the Houston metropolitan area.

The longevity tests have also raised questions about temporary stopovers. Specifically, what if a taxpayer moves from a foreign county to California, stays in California for a few months, and moves on to New York? Can this count as a single move? The tax court has generally found that each move is distinct. But the cases leave this open as a possibility. See, e.g., Chamberlin v. Comm’r , 78 T.C. 1136 (move from Hawaii to California to retire where the stop in California was to finish up retirement paperwork before moving on to New Mexico for retirement).

The work longevity tests can also prevent some taxpayers from being able to deduct moving expenses. Short-term and seasonal jobs are an example. Consider the case of a snowbird who moves from Illinois to Arizona each winter. They cannot deduct their moving expenses even if they take a part-time job in Arizona. They may be able to deduct their moving expenses to return to Illinois.

The same goes for a tax preparer who moves to a new city to take a job during the three-month tax season. If the tax season only lasts three months each year, the tax preparer will not be able to show that they worked at least 78 weeks in the new location. This could even be true if the tax preparer remains in the new city indefinitely as they would not have 78 weeks of work completed in a 39 week period.

How to Claim Moving Expenses on My Taxes?

Moving expenses are reported on Form 3903, Moving Expenses. This form is filed with your Form 1040, Individual Income Tax Return.

Circumstances Beyond The Taxpayer’s Control

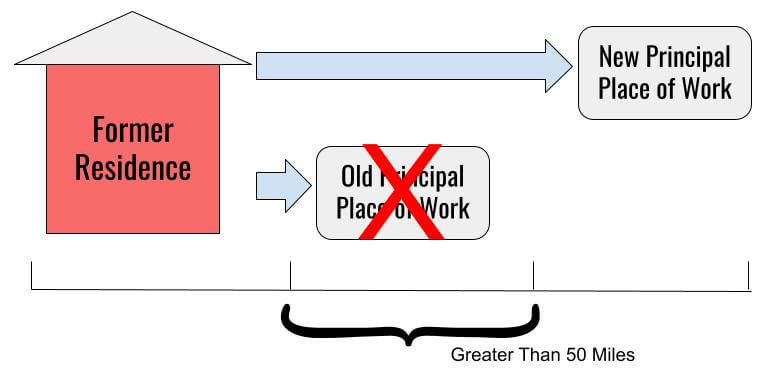

But what happens when there are circumstances that prevent the taxpayer from meeting either the distance tests or the work longevity tests? Can the IRS or the courts bend the rules? This brings us back to the issue in the present case.

The taxpayer in the present case moved from California to Hawaii. He only stayed at his job in Hawaii for a few months. He left his job as he didn’t feel that Hawaii was safe for his family. Thus, he moved back to California.

The moving expenses for the move to Hawaii did not qualify as the work longevity tests were not met. The expenses for the move back to California did not qualify as the taxpayer did not move back to California for a job. The taxpayer apparently testified that he moved back to California with no job.

If the facts were slightly different, the moving expense may have been allowable. For example, had the taxpayer intended to start a consulting job in California (either as a self-employed or sole proprietor), he could still have deducted his moving costs to return to California.

The Takeaway

Those who move for work should pause to consider the moving expense deduction rules. This can help ensure that this above-the-line deduction is available to offset the income or profits from their new job or business. A consultation with a tax attorney can help in this regard.

In 40 minutes, we'll teach you how to survive an IRS audit.

We'll explain how the IRS conducts audits and how to manage and close the audit.